History of the Royal Ontario Museum

The Royal Ontario Museum (ROM) was established on April 16, 1912, and officially opened to the public on March 19, 1914, by the Duke of Connaught. Initially governed by both the Government of Ontario and the University of Toronto, its first collections were transferred from the university and the Ontario Department of Education, originating from the Museum of Natural History and Fine Arts at the Toronto Normal School. The original building, which cost CA$400,000 to construct, housed five separate museums: Archaeology, Palaeontology, Mineralogy, Zoology, and Geology.

In 1947, the ROM's assets were transferred to the University of Toronto, but in 1968, the museum separated from the university to form an independent corporation. The McLaughlin Planetarium was added to the museum in 1968, following a CA$2 million donation from Colonel Samuel McLaughlin. However, the planetarium was closed in 1995 due to budget cuts and was eventually sold to the University of Toronto in 2009.

A second major addition, the Queen Elizabeth II Terrace Galleries, was constructed between 1978 and 1984 at a cost of CA$55 million. This expansion, designed as layered terraces, won a Governor-General's Award in Architecture.

Michael Lee-Chin Crystal

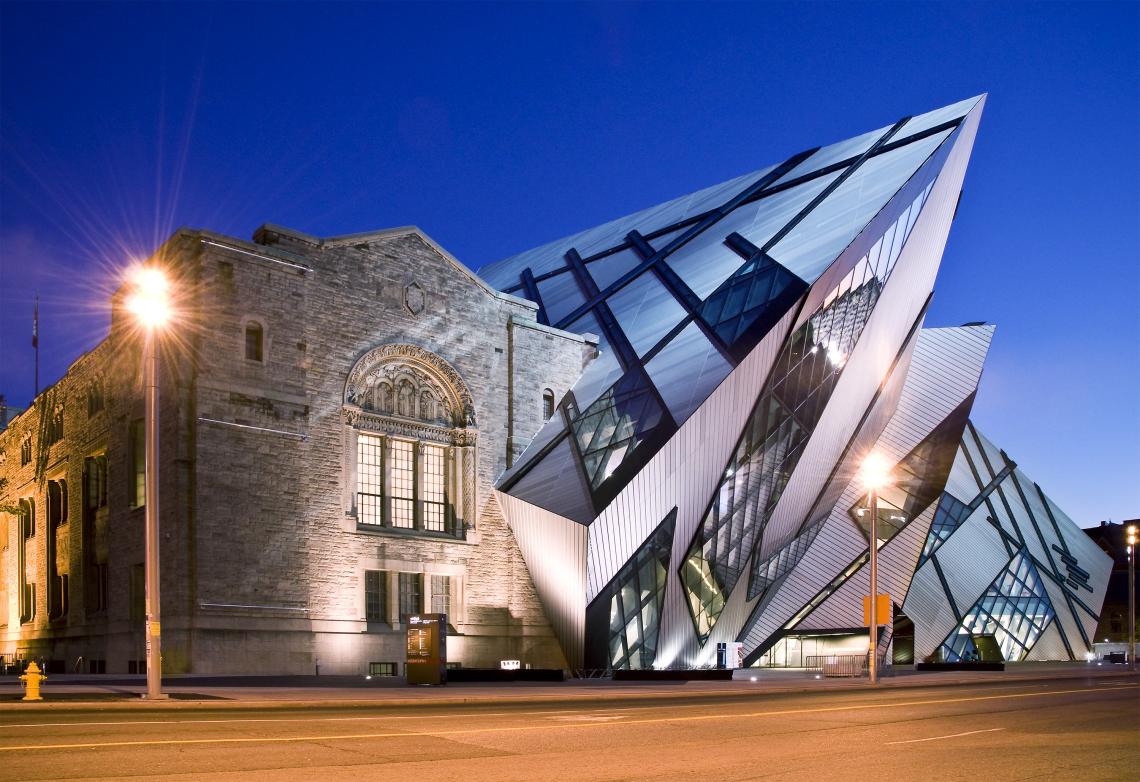

The Michael Lee-Chin Crystal is a striking architectural addition to the Royal Ontario Museum (ROM) in Toronto, completed in 2007. Designed by architect Daniel Libeskind, the deconstructivist style features bold, interlocking prismatic forms inspired by natural crystalline structures. Clad in aluminum and glass, the Crystal creates a modern contrast with the museum’s historic buildings, allowing natural light to illuminate the interior.

Inside, the spacious and dynamic galleries encourage exploration, with angular walls providing a unique backdrop for exhibits. The Crystal expanded the ROM’s exhibition space, including new public areas like a lobby, retail spaces, and a restaurant. Named after philanthropist Michael Lee-Chin, who donated CA$30 million to the project, the Crystal is now an iconic symbol of the ROM. The total cost of the Renaissance ROM project, including the Crystal, was approximately CA$270 million.

Galleries and Exponents

Originally, the Royal Ontario Museum featured five major galleries dedicated to archaeology, geology, mineralogy, paleontology, and zoology. The museum's exhibits were traditionally arranged in a static manner that saw little change since the Edwardian era. For instance, the insect exhibit, which remained until the 1970s, showcased specimens from various regions around the world in lengthy rows of glass cases. Within these cases, insects of the same genus were pinned, with only the species name and location provided as descriptions.

In the 1960s, it introduced more interpretive displays, like the original dinosaur gallery, featuring dynamic poses and backdrop paintings. This trend continued, with galleries becoming less static and more dynamic and interpretive. For instance, in the 1980s, The Bat Cave replicated a cave experience with sound systems and strobe lights as bats flew out.